Un-Earthed,

Un-Veiling

-

b. 1989) is a ceramic-based artist. She holds a BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (2009–13) and an MFA from the Oslo National Academy of the Arts (2021–23), where she was awarded the NK Student Prize in Oslo 2023.

Her artistic techniques and practice are grounded in a personal philosophy of seeking originality and materiality in everyday life, especially through clay—an element naturally given by the earth.

Park has been awarded the National 3-year Working Grant for Young Artists, as well as the Talente Preis 2024 – Meister der Zukunft from HWK für München und Oberbayern (Munich, Germany).

Her works are held in the collections of Nasjonalmuseet, KODE Bergen, UD (Ministry of Foreign Affairs), Oslo Kommune, and the Nordenfjeldske Kunstindustrimuseum (National Museum of Decorative Arts, Trondheim).

17th October -

06th December

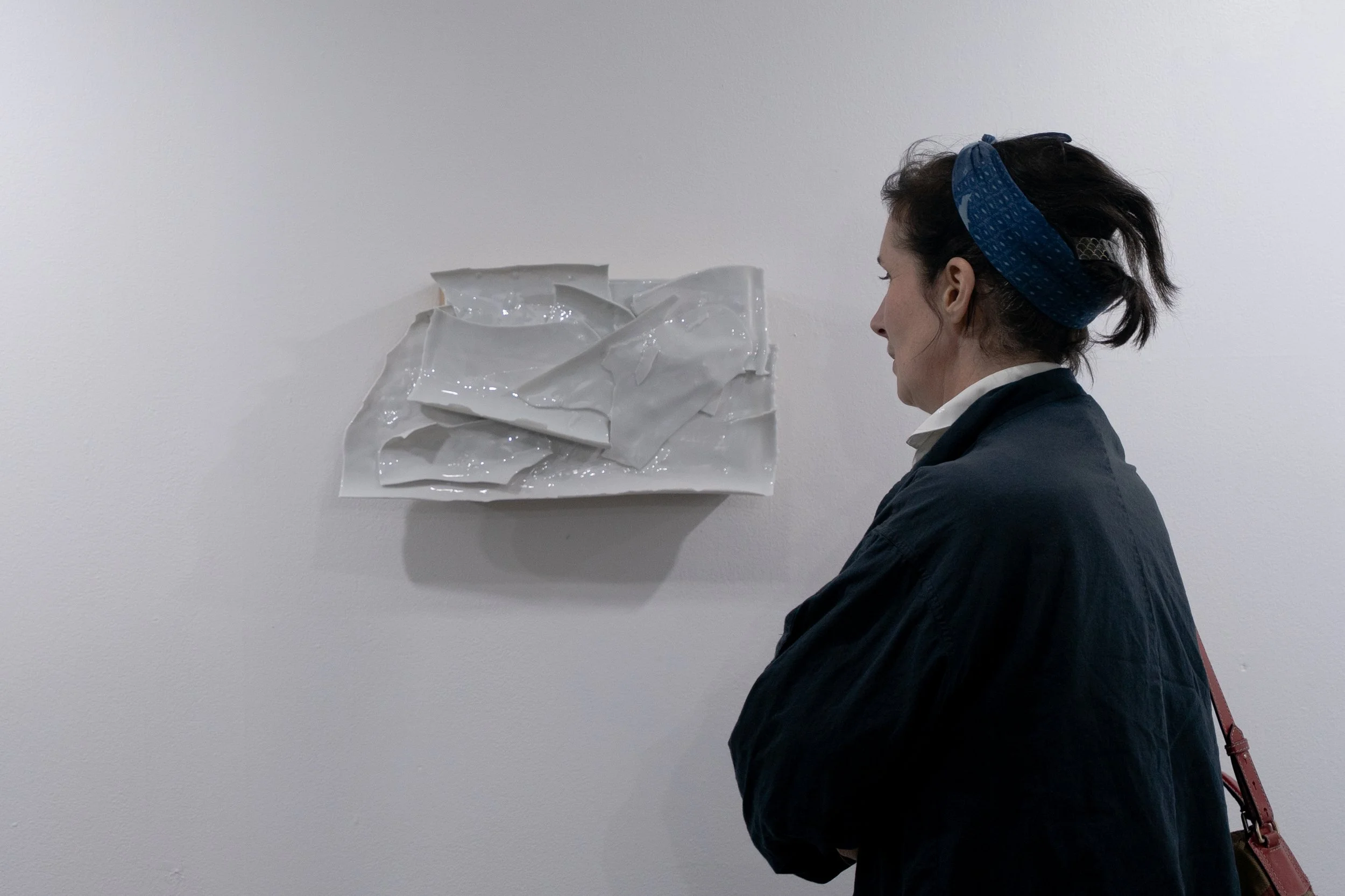

Some lovely moments from the opening last week with Lydia’s lustrous exhibition Un-Earthed, Un-veiling.

Also the opening speech:

Dear all, thanks for coming to the opening of what is probably our last exhibition of the year. I say probably because for those who know us – well, you know us. This is yet another highlight in our program this year, although we do treat every exhibition in the program as a highlight. But after the installation, I realised: well, this is really something.

I first encountered Lydia’s work at the Autumn Exhibition 2022 in Drammen. At that time she was still a master’s student at KHiO, but the quality of her work had already made a deep impression. Her ceramic and stoneware sculptures were certainly not the biggest pieces in the exhibition room, nor the most eye-catching with brilliant colour or outlandish form. But there was something there that captured me and kept me watching – qualities I didn’t expect to see coexisting in the same works by the same artist. I’ll come back to these later, so please stay with me a bit longer.

So when Lydia responded to our open call in 2023 for the Flex Point exhibition for East Asian artists newly graduated in Norway, I was beyond myself. That was also the first time Lydia showcased her work in Bergen, including four wall-based ceramic paintings and sculptures – very different from the works you see here today, but still highly recognisable by those aforementioned qualities. Lydia’s works were presented at Entrée, our collaborator for that exhibition. During the hectic installation and opening days we didn’t manage to have an extensive conversation, but we did manage to secure this opportunity to host her solo exhibition here and now. So we could say, we have been anticipating this show for two years.

And you can understand how glad I was when Lydia started to unpack her works and I recognised those things that remain, and even become enhanced, in her new pieces. Those pairs of qualities we might normally consider contradictory, impossible to coexist: simplicity and intricacy; tenderness and toughness. Porcelain layers that look so fragile we imagine breaking them with the tips of our fingers, yet so sharp they could easily cut and trigger aichmophobia – a fear of sharpness. A strong influence from the heavy, deep ceramic traditions of Korea and East Asia, yet a freshness, boldness, and innovative approach that bring ceramic art into the future.

Speaking of the future, it’s in the news every day, so it’s no news anymore that our world is becoming more and more polarised. All the arguments, the conflicts, the contradictions. Either black or white, left or right, East or West, socialist anarchy or imperialist authoritarian…ok, now you see how politically ignorant I am, so I should swing back to what I understand. I just understand that it’s becoming harder and harder to believe we can live together in a world with so many differences, so many opposites and dichotomies. But Lydia’s work shows us an alternative – where those contradictions and antonyms not only coexist in harmony but also support and strengthen each other. It helps us to understand that no matter how different we are, we need each other. It’s not a miracle, but a reality. That’s why I still believe – call me naive if you want – that art and craft can change the world when it’s at its most difficult time.

Last year Lydia won a prestigious prize in Munich – the Talente Prize – Meister der Zukunft (Master of the Future). I truly believe she brings, with her hands, her craft, her passion and creativity, hope for the future!

Interview

with Lydia

-

Clay has been a material I’ve worked with since my undergraduate studies. However, it wasn’t until around 2020 that I began to think about it in a different way. Until then, my focus had been solely on the physical aspects—how to handle and shape it. After taking a few years away from my practice, I returned to working with clay, wondering if I would still remember how to work with it. To my surprise, it came back to me effortlessly, as if my hands still remembered the process instinctively. Through that experience, I came to realize that clay closely resembles time itself. This insight has become the foundation of my current artistic practice. Clay has existed throughout every era; it quietly supports us beneath our feet, remains with us through both joyful and difficult times, and offers a grounding force from which we can reflect on the time ahead.

-

Yes, moving between countries has had both subtle and significant influences on the way I approach my ceramic practice.When I first studied ceramics in the U.S., I was introduced to the concept of sculptural ceramics. That experience helped me move beyond seeing ceramics as purely functional and instead view it as a language for expressing emotions and ideas. My professor’s supportive guidance and warm feedback gave me the confidence to explore that creative potential, which became a foundation for my practice. In contrast, in Korea, ceramics have traditionally been approached with a focus on functionality and heritage. As a student there, I found myself often questioning what kind of work I should be making, caught between tradition and personal expression. Later, in Norway, I encountered a very different perspective—one that values the process just as much as the final product. This shift encouraged me to dive deeper into the materiality of ceramics and experiment more boldly with glazes and surface treatments. I also began incorporating other materials such as metal and glass, which further expanded the possibilities of my work. In short, each country has offered me a distinct lens through which to view ceramics. These geographical and cultural transitions have shaped not only how I create, but also how I think about the medium—and ultimately, they’ve helped me form a more layered and reflective artistic voice.

-

I believe that both the visible and the invisible accumulate over time, ultimately shaping new changes and forms of existence. This belief is not only a part of my worldview but also a fundamental approach in my artistic practice. When I returned to working with clay after a long break, I was struck by how clearly my traces remained on its surface. That moment sparked a sense of curiosity in me—almost like that of a child. I noticed that the thinner I made the clay, the more vividly and realistically the textures I envisioned appeared on a single slab. This led me to a desire to leave behind traces of my moments and emotions in the clay—and to connect with them through the material. Through this process, I began to discover the organic beauty that emerges unintentionally and found ways to expand it into a sculptural language. That’s when I truly became fascinated by the idea of “layering.” At first glance, layering thin sheets of clay may seem simple, but it actually requires careful timing and sensitivity. The process depends on balancing weight, moisture, and my own bodily awareness. It demands a sense of discipline and problem-solving—like an ongoing dialogue with myself. Over time, my exploration of layering has evolved from a purely technical or formal approach to one that also embraces its metaphorical dimensions. The accumulation of time, memory, and traces—layer by layer—has become a way for me to shape not only the physical form but also a deeper sense of personal presence.

-

For me, emotion is not only a source of inspiration but also an essential element that naturally flows through the entire creative process. Even in the moment of shaping clay with my hands, I can feel unspoken emotions responding to the clay’s warmth and moisture, quietly embedding themselves into the surface and texture. Emotion is not just where the work begins—it becomes internalized through the way I handle materials and is deeply reflected in the final form of the piece.

-

I believe this question is closely related to a previous one. While I come from an East Asian background, I don’t consider myself to possess the same level of refined craftsmanship as many traditional ceramic artists from the region. I have deep admiration for those artisans, and at times, I feel a sense of regret that I haven’t cultivated that same level of technical skill. However, paradoxically, not having received a strictly traditional East Asian ceramic education has given me the space to reflect more adeeply on my own practice and identity. That process has become a driving force in shaping a unique artistic path for myself. I approach all cultural contexts with openness, and I carry a sincere respect for tradition. Perhaps because of this, my work is often described as carrying both Western sensibilities and an Eastern atmosphere—even when I don’t consciously intend it.

-

I believe this is something that many ceramic artists—not just myself—can relate to and genuinely enjoy. Of course, there are times when I feel satisfied with a predictable result, but by nature, I have a strong experimental spirit. Even when I cook, I rarely follow recipes exactly. Instead, I enjoy taking creative risks and try to embrace whatever outcome comes my way. Whether in ceramics or cooking, I find the greatest satisfaction when the result turns out to be even more spectacular than I imagined. That’s why I continue to experiment, again and again, as long as there’s room for repetition and refinement.

-

At the time, I was in Korea, so I didn’t even consider the possibility of attending, let alone imagine that this honourable award would be given to me. Receiving it feels not only like a great honour, but also like a solemn promise—a responsibility to continue creating with sincerity. Moving forward, I hope to keep exploring my own artistic language by focusing on the relationship with materials, the internalization of emotion, and the visualization of time. At the same time, I want to remain open to collaboration with fellow artists and to the ever-expanding possibilities of the ceramic medium. To honour this promise, I believe it is essential to embrace change, to keep asking questions, and to experiment without fear. I hope that by continuing this process with joy, my work can offer others a space for reflection and emotional connection.